My latest collection of poetry “Long Distance Poet” is available here>> download in PDF

Lord Nelson, Uncle Oliver and I: the Life and Death of Oliver Bainbridge (an Unacknowledged Casualty of the Death of Empire).

This book is now available here ‘Lord Nelson, Uncle Oliver and I’ in PDF

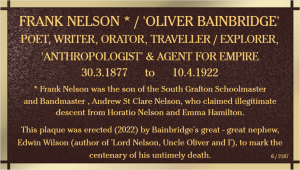

Frank Nelson, born 1877 at Smith’s Flat (Upper Copmanhurst), via Grafton, New South Wales, was the son of the pioneering bush schoolmaster, Andrew St Clare Nelson (who’d been a naval cadet with Prince Alfred, later Duke of Edinburgh, and claimed descent from Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton). A video of my talk to The State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW), about this biography is at this link.

Executive Summary

Lord Nelson Down Under?

The Life and Death of Oliver Bainbridge

(Frank Nelson/‘Oliver Bainbridge’ (1877 – 1922): Poet, Writer, Orator, Explorer, ‘Anthropologist’ & Spy, and purported Great Grandson of Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton)

by Edwin Wilson*

Frank Nelson was the Australian-born ‘streaking-star’ of our family, son of the pioneering bush schoolmaster, Andrew St Clare Nelson. To put this into some context, most of my other Colonial forebears (consisting of soldiers, sailors, emancipist farmers and fishermen) had been illiterate (and my father’s occupation, as listed on his death certificate (1942) had been ‘tractor driver’).

As Frank’s father, Andrew Nelson had been both literate and musical (and ‘spoke seven different languages’); this made him stand out in my family tree as a lighthouse before GPS.

What made Andrew Nelson even more remarkable was his claim to (illegitimate) descent from Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton. Family legend was he’d been sent to Naval College (by the then Lord Nelson), and had sailed with an English Prince (one of the sons of Queen Victoria).

I had assumed that Andrew would have been a child of one of the children of Horatia Nelson, born c. 29 January 1801, illegitimate daughter of Horatio Nelson and Lady (Emma) Hamilton. Emma, accompanied by Francis Oliver, had delivered Horatia (concealed in a large muff) in the dead of night to the home of a wet-nurse called Mrs Gibson (in February 1801). Nelson and Emma were absent for the christening (arranged by Mrs Gibson). The child (of ‘no known parentage’, the equivalent notation as used when Andrew married), had been named Horatia Nelson Thompson, god-parents Lady Hamilton and Lord Nelson (when ‘god-child’ was often code for ‘illegitimate’ in the 19th Century).

Nelson had been at sea when the child was born, and Emma had lied about the date of birth (29 October 1800, to put her conveniently out of the country). Nelson had used the name ‘Thompson/Thomson’ as a ruse in his letters to Emma. Admiral Thompson of Portsmouth Dockyards had then been persuaded to pretend to be the ‘fake father’, and it was not until 50 years after the birth of Horatia that her parentage had been proven publically. [i]

Horatia had been given Royal Licence (30 September 1806) to use the name ‘Nelson’, and for the record was reported to have spoken five different languages. Horatia went on to marry the Rev. Philip Ward. They had nine children, one of whom died young. I had first thought that her eldest child, Horatio Nelson Ward (1822 – 1888) who had married Elizabeth Blandy, could have possibly fathered Andrew Nelson.

My first real break came in 1994, when I found a vital clue in Winifred Gérin’s (1970) book, Horatia Nelson. Winifred Gérin, b. 1901 (who had written extensively on the Bronte sisters and their brother Branwell), had been assisted in Horatia’s book by Sir William Dickson, [ii] one of Nelson’s great grandchildren, who would have had access to family stories. Now I know this sounds like the Hollywood rendition of some gothic novel, but according to Winifred Gérin (assisted by William Dickson), Horatia had been part of a twin birth, and both twins had survived. More evidence of the birth of twins comes from a letter from Nelson to Emma (23 February 1801), when he had written (bearing in mind the twins were probably born 29 January 1801), and still using the Thompson/Thomson ruse, anticipating his return that ‘I dare say that twins will again be the fruit of their [our?] union’. [iii] Sadly, Nelson had destroyed all of Emma’s letters to him (as requested). Emma had subsequently lied to Nelson (again), saying one of the twin girls had died, but she had been committed to St Pancras Foundling Hospital, [iv] and christened Emma Hamilton.

Flora Fraser records that on the anniversary of the Battle of Copenhagen (19 April 1801) a foundling child at St Pancras had been christened Emma (Mary Jane?) Hamilton, god-parents Lady Hamilton and Lord Nelson, [v] in the presence of Lady Hamilton, Sir William Hamilton (and others, unspecified). The symmetry of this christening with that of Horatia, and the pairing of Emma with the female form of Horatio is most significant to me.

The Records of the Foundling Hospital, Church of England, St Pancras, show that on 19 April 1801, child number 18643 (of a batch of six) was christened Emma (Mary Jane?) Hamilton by the Reverend C.T. Heathcote (no other information supplied). [vi] Another child had been christened Baltic Nelson on this day, a red herring perhaps, to draw press hounds from Nelson’s bloodline, as we now know the establishment had tried so hard to hide the true parentage of Horatia. What chance the poor foundling?

There is a potential problem here, in so far as ‘Emma Hamilton’ crops up more than once in the records. Emma’s first illegitimate child (most probably fathered by Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh), had been called Emma Hamilton, and had changed her name to Anne Carew (perhaps with a new Emma Hamilton on the scene). Even the Nubian servant/slave (called Fatima, brought back by Nelson from the Battle of the Nile), had been christened (26 April 1802, aged about 20 years), as Fatima Emma Charlotte Nelson Hamilton. [vii]

According to John Sugden, the foundling child, Emma Hamilton, was the daughter of William and Mary James. [viii] But given the ‘fake father’ now known to have been established for Horatia, a symmetry argument of ‘track-covering’ surely applies, and why would Lady Hamilton be dragging her poor husband along to be god-mother for someone else’s child? I feel a sense of pain and outrage even now, on that poor child’s behalf, if Winnifred Gérin’s story is indeed true, how could a mother abandon one child over another? Emma’s choice indeed, when raising an illegitimate child at the time would have been hard enough, then two would have been virtually impossible.

The foundling-child was adopted out to Mrs Sarah Snelling of Chertsey, Surrey, close to Nelsons home of ‘Merton’), who wrote(20 May 1801) ‘to acquaint Lady Hamilton that the child she had obtained from the foundling [was] well and much grown’. [ix]

Some time later Horatia Nelson Ward had arranged for her husband to write to the Vicar of Chertsey, who confirmed Mrs Snelling (nee Field) and her sawyer husband had received the child Emma Hamilton (and three boys) from the Foundling Hospital. [x] It is not known if Horatia ever had contact with her twin, but this proves she was aware of her existence, and this is something that William Dickson may have known of too.

On 21 June 1820, Emma (Mary Jane) Hamilton (illiterate, despite such a posh-sounding name, but in keeping with a foundling child being raised in a working class family at the time) married William Gibson, sailor (by Banns) at Newington, St Mary, Surrey (and one wonders if he was related to the wet-nurse Mrs Gibson?).

No record for the birth of Andrew Nelson/Gibson has been found for 1840 in St Catherine’s Register, London. Accord to naval records Andrew’s residence (in 1857, at his time of signing up on the Cambrian), had been Guernsey (Channel Islands), and his trade as ‘brought up to’ was ‘[the] sea’.

The best match I was able to make at the time (from the extensive IGI records of the Church of the Latter Day Saints), and given the Scottish connection of the name ‘Andrew’ (with father William and mother Mary Hamilton), the following baptism had jumped out at me:

Baptism, Andrew Gibson, 7 December 1840, Cullcross County, District of Perth, Scotland

William Gibson turned out to be a sailor, supporting that Andrew’s ‘trade brought up to’ had been [the] sea, and sailing would have given them mobility.

The original Emma Hamilton had died in 1815 (in Calais, with the enemy), and having sold Nelson’s letters for profit was decidedly unpopular in England, so her daughter may well have reverted to her second name. I am conscious that this is all speculation, and the weakest link in the chain to date, that would need to be checked by later historians.

The same IGI records have attributed at least three sisters (to Andrew) from this marriage, and along the way William’s occupation seems to have progressed to ‘gentleman’

Family sources confirm that Andrew had a least three sisters. The eldest had been Emily (‘spelt in the French way’, and essentially another ‘Emma’ in the family tree, and then Andrew had called his eldest child Emily (known as aunty Em)), and I believe this youngest sister was called Anne. There had been a collection of letters in the family (to Andrew, from his sisters, in French), sadly destroyed by a lady who lived at Byron Bay.

None of this affects what Andrew had claimed in any way, or the exploits of his son, Oliver Bainbridge. After a lifetime of Nelson references I passionately believe Andrew Nelson had been telling the truth. His granddaughter, Nina (with only a basic primary school education and who did not frequent libraries) had a head full of stories about Lord Nelson and Lady Hamilton. Details of Andrew’s time in the Royal Navy have since been found. [xi] And given that Horatia had had Royal Licence to use the name ‘Nelson’, once more, by symmetry arguments I contend Andrew could have adopted the name Nelson on entering the Royal Navy.

* * *

If so then Andrew was probably ‘advanced’ by the Nelson Memorial Fund, a public appeal ‘established (with the approval of Horatia Nelson) in 1847 …. [and] … Queen Victoria had settled pensions of £100 a year on each of Horatia’s three daughters, and two of her five sons not already … in careers were given appointments that established them for life’. Seven years later (in 1856) the Nelson Memorial Fund had ‘successfully won grants and advancement first for Horatia’s sons, and then for her daughters’. [xii]

Andrew Nelson signed up for the Cambrian in 1857, [xiii] at the same time that Horatia’s two younger sons, William and Phillip had been sent to India as naval cadets, almost in parallel with Andrew’s story. [xiv]

Andrew had not liked the navy; he had been bullied there (because of the purported Nelson connection), and his commission ‘bought out’ in 1861. He came to Australia in 1862, calling himself a ‘gentleman’, and ended up at the First Falls Inn, out of Grafton NSW. The navy records (in Kew, London) [xv] show Andrew had been receiving ‘foreign remittances’, with some later apparent contributions when he was in Australia, almost as if he’d been paid to keep away.

In 1868 there had been big celebrations in Sydney, on the arrival of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, as master of the Galatea. Alfred had been sent to Naval College in 1856. Given the small number of the intake of cadets each year, spread over a normal training period in the one locality (and given that Alfred was reported as being interested in music, as Andrew certainly was), the paths of these two young men would have crossed sometime.

Dr Graeme Skinner (University of Sydney) has listed Andrew as a Colonial Composer in his own right, who had produced works for the first program of his newly-formed Grafton Amateur Band (in November 1867), closely followed by his ‘Galatea Polka Mazurka’, as a patriotic nod to an old classmate of his naval college days. Alfred shot a lot of cute furry animals during his Australian visit, and planted a tree in the Sydney Botanic Gardens (still there in my time at the Gardens). The day after planting this tree Prince Alfred had been shot at Clontarf, in an attempted Sinn Fein (IRA) assassination attempt.

Andrew Nelson called himself ‘St Clare’ Nelson more in later life, perhaps for status reasons. He had certainly been Headmaster and Bandmaster of South Grafton, a steady family man, and not an escaped convict, fantasist, or illywhacker. Old white Colonial Australia (set up as a dumping ground for the oppressed, displaced, and dispossessed of Empire, after the loss of the American Colonies, and around the time of the French Revolution), had had a lot of them.

* * *

As a child growing up on the then-isolated far north coast I had heard of the exploits of Andrew St Clare Nelson and his son Frank (Oliver Bainbridge) from my mother’s mother (Jessie Smith, nee Neale), and her sister, Nina Shore (nee Neale), whose mother had been Elizabeth Nelson (daughter of Andrew St Clare Nelson). Nina used to refer to her Uncle Oliver as a ‘Wandering Bard’, while Nina’s sister, my granny Smith always said he was some sort of spy. The young tend to accept the world as they find it, so to me it was quite unremarkable that half my relatives were ‘related to Lord Nelson’, and Uncle Oliver had been a poet and a spy.

In the days before television, families would sometimes sit and talk after a meal, and I was enthralled by tall tales of the exploits of Uncle Oliver (and there is no doubt that Bainbridge had been part inspiration (to one so totally unintimidated by the weight of literature and art), that I too could be a poet (and a painter) when I grew up).

* * *

The Nelson legend had given the farm boy both drive and aspiration, that in hindsight could have been a case of ‘blood will out’. In 1968 I was lecturing (in Science method) at Armidale Teachers’ College. At afternoon tea I had been talking to a colleague, historian Lionel Gilbert, and told him about the Nelson Legend.

‘You must try to research that,’ he had said, ‘and publish it,’ and he gave me my first pointers.

It was slow going at first, without the Internet. Nina sadly had just died, and her husband did not have her memory of stories. Returning to Sydney in 1972, I looked for Bainbridge’s books in second hand shops, with no results. My first breakthrough came with the card index at the State Library of New South Wales, with reference to some Bainbridge letters and publications. To hold one of his early books in my hand, The Lessons of the Anglo-American Peace Centenary, a rather dry tome about the approaching centenary of the mostly forgotten Anglo-American war of 1812-14, was an incredible experience. I was 29 years old. I had found my avocation, and would go on to publish more than thirty books (now housed in that same library, along with my Woodbine files, manuscripts, and Creative Journals).

In 1983 I made contact with Nina’s cousin, Ivy Creasey of Grafton, another granddaughter of Andrew Nelson, who had some of Nina’s photos (from Ron (Roy) Evans of South Grafton).

In 1994 I spent a very productive week in the old British Library (at the top of the British Museum), and the Archives office (in Kew), then came back and I read Winifred Gérin’s (1970) breakthrough book, and made a series of important discoveries through the IGI.

In 1995, through Ron Evans I had met my fellow-researching Nelson cousin, Patricia Wightley (Sister Mary Joseph (‘Sister Pat’)), whose mother had told her ‘the blood of Lord Nelson flows through your veins’ (precisely the same words that Nina had said to me). She too had followed the paper trail, and on her own researching trip to England had stayed in the convent where Anne Carew had later resided, and had become ‘a valuable member of that community’. Pat and I pooled our resources and published two joint papers in Australian Folklore (University of New England) in 1996 and 1998, and I powered on for the next twenty years.

As a result of the ‘Folklore’ publications I was contacted by Barton Oliver Bainbridge (from Oregon, USA), grandson of Oliver Bainbridge. The American material helped fill in some important gaps in our narrative. Barton’s son Bryant then scanned significant papers and photographs for me, as used in our 2013 monograph that came out just after Barton died.

A cache of Bainbridge letters (in the Huntington Library in California) was then located (by Miles Bainbridge (grandson of Barton Oliver)). And then I discovered TROVE (the digitisation of old newspapers in Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America). For the first time ever I could match the ‘where’ with the ‘when’ (and was made aware of the incredible value of local/regional newspapers), resulting in the first detailed timeline of Bainbridge’s life.

In 2017, after almost 50 years of hard work (seeking documentation of events, cross-references and linkages) I published Lord Nelson, Uncle Oliver and I (with more than 1,500 endnotes, and acknowledging research assistance from Patricia Wightley (Sister Mary Joseph/’Sister Pat’)), now posted for free downloading on my Website.

This book is rather ‘dense’, with a lot of side stories. This is a chronological ‘Executive Summary’ of Frank Nelson’s story (linking together the Nelson legend, Bainbridge’s slightly nefarious ‘career’ and naval references, and his untimely end).

* * *

Frank Nelson had been born at Upper Copmanhurst in 1877, deep in the Australian wilderness of rocks and trees. As a child in South Grafton he had played a ‘footballer’ in a stage production, and had taken the man in the local Shooting Gallery to court for short-changing him of his sovereign (using the old ‘hole in the pocket’ trick with his trousers tucked into his boot). Having a strong will Frank had clashed with his father, and left school at about age 12, for a lowly job as a clerk in the South Graton Post Office. Tiring of life in the slow lane, and perhaps with a sense of ‘Nelson entitlement’, he stole money from some letters at the Post Office, was caught, tried, and sentenced to spent a year in Grafton Gaol.

On his release (October 1894, aged 17 years) his father threw him out of the family home, for ‘disgracing the name of Nelson’. That night, as he walked away, the frogs had started croaking in a local ponds, ‘Dwark ork, dwark ork’. ‘I know it’s a dark walk you bastards’, he is reputed to have said, ‘You don’t have to rub it in’, and it’s an indication of the strength of his personality that this story had been retained in family folklore now, well in excess of a hundred years.

Now homeless, he had lived for a time in the native camp, the start of his interest in ‘anthropology’ and a steep learning curve of ‘toughening him up’, and the beginning of his life of ‘wandering’. According to Ivy Creasey he went to New Zealand after that (in 1895), to ‘study Maori life’, then on to New Guinea (1896).

In February 1897 (still calling himself Frank Nelson) he gave a public lecture in South Grafton about ‘Crime and its Cure’, that was reasonably well received, and the beginning of a pattern of making a living by charging people to come along to hear him speak.

His Grafton-based friend and mentor, Doctor Thomas Henry, criminologist and Shakespeare scholar (assumed to have met Bainbridge through the Grafton Gaol connection), most probably helped him prepare his initial talk, and may even have ‘recruited’ him for his subsequent ‘career’ (because of his interesting travels and associations), and who, towards the end of his life, worked as a ship’s radio officer and read books and travelled the world. [xvi] Henry had studied medicine at Edinburgh with George Ernest ‘Chinese’ Morrison (see later), and Arthur Conon Doyle (of Sherlock Homes fame, also see later in the Bainbridge story). Morrison had been speared while exploring in the highlands of in New Guinea, and had gone to Edinburgh to have the offending article removed, and had stayed on to study medicine.

About March 1897 Bainbridge ‘left town under a cloud’, from a request to procure the head of an old man for ‘anthropological research’ (at a time when the bodies of recently deceased aborigines were being dug up in Tasmania, and sent to Museums all around the world), most probably influenced by the displays of mud-covered skulls with shell eyes, as found in Men’s Houses in New Guinea.

London had called. He probably worked his passage on a cargo ship (as his two boys from his second marriage had later done, working their passage to Australia). It’s incredibly hard for me to imagine a ‘nobody’ (with limited formal education, born deep in a Colonial backwater, and having spent a year in Grafton Gaol to boot) as making it in Victorian/Edwardian London of the late 1800s/early 1900s, without more than talent, ego, self-belief, and gall?

According to his grandson Barton, Bainbridge had met the young Winston Churchill in Africa (most probably at the Battle of Atbara (24 August 1898), and/or the Battle of Omdurman (2 September 1898)). [xvii] Churchill had certainly fought in the Sudan. Bainbridge had seen the fighting, [xviii] and had been shot and wounded there, then tried his hand as ‘war correspondent’, by reporting on the fanatical fighting of the Dervishers (wire service, December 1898), in a local (Grafton) paper. [xix] Churchill went on to become a war correspondent (in the Second Boer War, sometime after October 1898), then went to India to stay with Viceroy Lord Curzon after the fighting ended. This is a pattern that Bainbridge was later to follow, with extended periods of stay/work in India, through forging an association with Lord Curzon (and his replacement as Viceroy, Lord Minto). Curzon was an old naval name, and the 2nd Lord Minto had been Frist Lord of the Admiralty (1835 -1841).

Lord Curzon had travelled extensively in his youth (through Russia, Persia, Afghanistan, Siam (Thailand), French Indochina (Vietnam), and Korea), and had written books on policy implications relating to these latter two regions (with turbulence through last century, right up to our present time). Bainbridge was later to correspondence with Lord Curzon, and Sir Walter Roper Lawrence (his private secretary from his time of Viceroy of India), on at least four occasions between 1907 and 1915, and spent time in India towards the end of 1905 (at the beginning of Lord Minto’s time as Viceroy, with a much longer visit starting in April 1910).

Churchill had been writing his book, The River War (1898), when he and Bainbridge had apparently met. Back in Australia (1898) Bainbridge was immodestly talking of writing a great book on his travels in four languages: English, French, German and Russian (implying Russian was one of the languages he was competent in), and later went on to write a number of books, including the relatively lightweight, The Heart of China (1912), and the more substantial India Today (1913).

Frank certainly had ‘an aptitude for languages’. His father would have taught him French. As a child at South Grafton he had been exposed to Irish Gaelic and German (most helpful to him with his later interest in German Secret Societies in Samoa and America). According to an article (1997) in the Sydney Morning Herald, British agents had been ordered to infiltrate Irish-American groups (and possibly German associations, because of their support for Ireland) at the end of the 19th Century for fear of transatlantic support for republicanism in Ireland. It is thought that an Irish revolt could trigger a similar revolt in India. Britain’s chief agent in America signed himself ‘Z’, and to this day the names of special informants [were] still blacked out. [xx]

Winston Churchill may have been an influencer too, but perhaps, just perhaps the purported Nelson connection, if this were true, had also opened doors for him. And if the Nelson story were indeed true, then Churchill would have been an attenuated cousin (through the Walpole line), and given Bainbridge’s incredible capacity for detail, this is something he possibly may have known.

Frank Nelson was an autodidact no doubt, and a brilliant, if somewhat flawed character and a strange mix in so far as he was a ‘truth-teller’, who sometimes told brutal truth to power like some court jester (not toned down with social or political constraint). Contrasted with this he told many lies throughout his early life, saying he had a BA (later upgraded to MA) from Oxford University, and passing himself off as the brother of an English Earl, with a Seat waiting for him in the British Houses of Parliament (House of Lords?), when the ‘Seat’ would have gone to his brother and not him (and his occasional mentions of ‘Lady Bainbridge’ were uncannily like Nina’s stories of Lady Hamilton). My main thought here, is that if Bainbridge was indeed a spy (as the considerable evidence in this essay will surely indicate), then deception would have been part of his game. In this context I have read that Winston Churchill was involved in recruiting for some nefarious activities during World War I (and World War II as well), and as a policy had chosen risk-takers for such tasks.

Now was the time our Frank took on his new persona and new identity (of ‘Oliver Bainbridge’) and relentlessly travelled as Soldier of Fortune, and ‘Agent’ of Empire.

* * *

In 1897 he had commenced a world-walking tour (perhaps as a nod to his Grafton mentor’s friend and legendary walker, ‘Chinese’ Morrison), setting out from London with his pistol and his dog ‘Barry Moore’ (spelt ‘Barrimore’ in some sources), going first to France, Spain, the rest of Europe, Scandinavia, Russia, the Balkans, India and Ceylon. This ‘penniless poet’, now travelling to exotic places, had access to the relatively new (and useful spying technology of a camera), that would have been quite expensive at the time, and heavy, and cumbersome (as we are talking about an age of glass negatives here), so it was almost as if someone else was ‘carrying this load’ for him.

In Russia he had been imprisoned (for nine days), and tortured for alleged spying activities, from him having drawn his pistol and having struck a military officer, [xxi] yet somehow had representation from the British Consul, who, according to the young Bainbridge in one slightly ‘purple’ account, had ‘taken a British flag from under his coat, and spread it over the tortured man, and gave the Russian authorities ten minutes in which to release him’. [xxii]

Being a slow learner he was then shot in the back and arrested as a spy (in Asiatic Turkey) for having a camera (he said he had taken a photograph of the belle of a little city [xxiii] ), tortured and found guilty and sentenced to death by shooting. The Sultan had intervened because of his youth (being still only twenty), and he had been released, [xxiv] and bore the scars of this torture (on the bottom of his feet) for the rest of his life. [xxv]

With all the energy, and fearless drive and arrogance of youth he had pushed on. While looking for specimens in the Veyan Suda jungle of Ceylon he had been lost for three days, and took fever and could have died, [xxvi] (with four different fevers reported in four different countries). In 1898 he continued his travels: through Burma, Siam (Thailand), Cochin China (then a French colony, comprising about a third of Vietnam), China, Japan, Gilbert Islands, Fiji, Java, and on to Africa (where he reputedly met Churchill, and had been wounded in the Sudan War).

In Australia (December 1898 and into 1899) he conducted a well-documented speaking tour (as ‘Wandering Bard, BA’) down eastern New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, and South and North Islands of New Zealand (more details in Lord Nelson, Uncle Oliver and I). He had caused a big stir when he blew into Wellington, New Zealand (c. 3 July 1899), and was certainly not on top of his game at his ‘entertainments’ at the local Opera House. A local doctor had stood up and moved that the visitor ‘not be further heard’ (linking back to earlier problems in Nelson and Blenheim (at the northern end of the South Island)). A local lawyer then moved an amendment (most prescient in hindsight), that the ‘cheeky man be shot’. Bainbridge left town early next morning. [xxvii]

* * *

From here on Bainbridge seemed to keep on popping up at all the little wars (and not so little wars, or talk of wars) around the globe, with a lot of them about to keep him occupied. In July 1898 America had annexed the Polynesian Kingdom of Hawaii (very significant in World War II). In December of that same year Spain had ceded the Philippines to America (at the end of the Spanish-American war), tilting American influence in the western Pacific for the first time. By early 1899, German, British, and American warships had been fighting for the control of German Samoa. Then Germany annexed Bougainville into German New Guinea, having earlier annexed Nauru (1888).

The American flag was raised on the Samoan island of Tutila in February 1900. In April 1900, Bainbridge (just out of hospital from his purported accidental ‘weasel-shooting’ incident, unless this was some sort of ‘fabrication’ for something more serious) and talented musician, Jessie Teasdale, ‘go exploring’ as ‘man and wife’ to Samoa, and off the New Zealand ‘newspaper radar’ for four months (with a later (1902) piece by Bainbridge in the Los Angeles Herald [xxviii] with photographs of happy natives in Pago Pago, under the caption of ‘America’s New Possession in the Pacific’).

Next thing a Japanese source, as reported in America (5 August 1900) said that ‘Mr and Mrs Bainbridge’ (this was very much his later style with his second wife) were among a group of foreigners trapped in the American Legation in Peking (Beijing) [xxix], where Bainbridge’s Grafton mentor Dr Henry’s university friend, George Ernest (‘Chinese’) Morrison, just happened to be a ‘Correspondent’. A Mr and Mrs Squires (and four children) were also reported to be in the American legation. [xxx] As a point of linkage, a Mr and Mrs Squires attended a function (29 September 1921) with Mr and Mrs Bainbridge (second Mrs Bainbridge) hosted by Mrs Askin-Hetzell at the (Sydney) Metropole Hotel, and Oliver Squires is recorded as being at Oliver’s funeral. And as ‘Squires’ is not such a common surname, this could be more than coincidence.

The implication here is that Bainbridge and Jessie, because of Bainbridge’s purported ‘intelligence’ links, had ‘hitched’ a ride to China on an American warship from Samoa. The American President McKinley was then shot, lingered and died (14 September 1900), and Bainbridge wrote an elegy for him.

Had Bainbridge and Jessie Teasdale been in China? Nina always said he had been to the Boxer Rebellion, and Bainbridge brought back a pet monkey back to New Zealand from the Samoan trip, for Jessie’s cousin, Hector Bolitho (which could well have come from China, as there are no wild monkeys in the South Pacific). [xxxi]

Just five years later (17 November 1906), Consul-General Sir Pelham Warren presided over a Bainbridge talk in Shanghai (northern China). Pelham Laid Warren, as Diplomat (in the China Consular Service) in the Boxer Rebellion, had played a critical role in averting the slaughter of foreigners in the various Legations in Peking/Beijing, and could have met Bainbridge then. In his retirement (in Sidmouth, Devon) Warren had often visited George Ernest Morrison to reminisce about their China days. As an interesting aside, the memoir of ‘Chinese’ Morrison (collated after his death by his widow), had been suppressed by British Intelligence (with echoes of the 1990s ‘Spycatcher’ case).

In the Huntington archive [xxxii] there are three ‘political’ letters to Bainbridge from Sir Alfred Gaselee (who had led the successful multi-national force into Peking/Beijing in 1900 to protect the diplomatic and foreign nationals). Significantly, in one letter Gaselee is declining to contribute to something Bainbridge was working on, on the grounds of a shocking memory, and not having kept a diary (of that time?).

More evidence of a 1900 China visit comes from the American family photographs and newspaper clippings. Most compelling are Bainbridge photographs of the Forbidden City (including Chien Lung’s ‘portion’ and his home (with a marble gargoyle for water drainage)), and the Gates to the ‘Temple of Azure Clouds’ (on the western hills outside Peking/Beijing), and a formal photograph of a young Bainbridge with Prince Pu Lu (location unknown). More indirect evidence comes from a promotional piece associated with a lecture at Hull, England (28 February 1918), saying ‘Bainbridge was as much at home in Papua or Peking’, [xxxiii] on the assumption that Bainbridge would have told them this when they were compiling the advertising flyer.

And all this in just two years after his purported meeting with Winston Churchill at the Battle of Omdurman (1898). You get the drift.

* * *

After a New Zealand marriage (1 November 1900), Bainbridge (now calling himself ‘King of Tramps’) and Jessie ‘explored’ the Fiji group, returned to Samoa [xxxiv] (confirming the earlier 1900 visit), then visited the Cook Islands, Tahiti, Hawaii (when tramping was not so romantic for two).

President McKinely had been replaced by Spanish War hero, Vice-President Theodore Roosevelt, a naval tragic, who had written The Naval War of 1812 (the almost standard text about the 1812- 1814 Anglo-American Naval War. One of his early Presidential moves was a take-over of the aborted French project to build the Panama Canal, and Roosevelt was the driving force behind the establishment of the modern American fleet.

In January 1902 Britain signed a naval treaty with Japan (thus freeing up her fleet to concentrate on the growing Grand Fleet of Germany in the Atlantic), and Japan was to become an ally in World War I. Bainbridge then pops up in British Columbia (Canada, sometime before July 1902), to be entertained by the Governor-General Lord Minto (who went on to become Viceroy of India). Bainbridge and Jessie then ‘explore’ America, where Jessie had appeared in musical recitals with De Konski, Rafaleluski, Weigaud, Lillian Norman, and had been soloist for the Boston Concert Company, [xxxv] gravitating to New York, where Jessie was sketched as a ‘New Woman’ by Charles Dana Gibson. [xxxvi]

In January 1903 the Hay-Herrain Treaty (between America and Columbia) was signed. Panamanian rebels want to separate from Columbia (2 November 1903). Roosevelt supports the rebels, sending in US warships to prevent Columbian troop movements. Panama declares its independence (3 November 1903), and America signs the Hay-Burnan-Varilla Treaty with Panama (6 November 1903).

11 September, Bainbridge’s son Wallace Campbell St Clair (variant spelling to Andrew St Clare) Bainbridge, was born in New York. [xxxvii]

28 November 1903 Bainbridge is in Washington, for an audience with President Roosevelt and Secretary Shaw. It is very hard to imagine the President of the United States (at the time of the Panama crisis) would want to be having afternoon tea with a visiting ‘tramp’, unless there was some subtext. Once more I propose it could be the Nelson connection (plus Roosevelt’s great interest in the 1812 – 1814 Anglo-American Naval War), as Bainbridge was later appointed to work with the well-connected American, Canadian, and English Committees, as editor of a proposed propaganda book, The Lessons of the Anglo-American Peace Centenary, projecting for 1914. On p. 24 of this book it confirms that a most important work of the American Committee was the ‘re-writing of the American school-books, in which Great Britain will not be described as the enemy of America, but her staunchest friend … [according to] … the Monroe Doctrine’.

Roosevelt was Honorary Chairman of the American Committee for this project. Despite the ‘Love and Peace’ references, and Bainbridge’s later associations with various Peace Movements, I have no doubt he was a Hawk pretending to be a Dove, with considerable interest in the details of naval wars over the years, plus military psychology and strategy (as from Little Stories for Other Wars). Other Bainbridge naval linkages (apart from those already mentioned) include letters to: Sir Almeric Fitzroy (naval family connections), Sir Charles Parry (whose grandmother came from the naval family of Lord Gambier, Admiral of the British Fleet), Lord George Francis Hamilton (First Lord of the Admiralty, 18185/6 and 1886/92), Lord William Palmer Selborne (First Lord of the Admiralty, 1900), and to both Admiral Sir David Bentley and Admiral Sir John Jellicoe (in the context of the naval battle of Horn Reef in World War I).

Back in December 1903, and almost as a side show British and Indian troops led by Francis Younghusband temporarily invaded (Until September 1904). Younghusband, as a young army officer (like the young Charles Lamington), had been an ‘explorer’, crossing the deserts of Central Asia (ostensibly to survey the geography), when his real purpose had been to ascertain the strength a Russia’s physical threats to British India. Remind you of anyone? Younghusband later became President of the Royal Geographical Society. Bainbridge’s election to Member of this Society was confirmed in an (undated) letter from William Martin Conway. [xxxviii] His election to Fellow (1 May 1907) was reported in The Times, London.

All this pressure had been too much for the marriage, and in December Bainbridge deserts his family ‘for another woman’, and his wife and child are ‘compelled to return to New Zealand’ where they lived with relatives. [xxxix]

8 February 1904, marked the start of the Russo-Japanese War, in which the Imperial Japanese Navy annihilated the Russian Fleet.

8 April 1904, ‘Entente Cordiale’ between Britain and her traditional enemy of France.

4 May 1904, America takes control of the Canal Property in Panama.

June 1904 Bainbridge is back in London. Did he visit Tibet on his way back from New York (or was it later when he was in India, in 1906)? While in London, and in the presence of King Edward, he gave a special posthumous address to Queen Victoria from a number of Maori Chiefs. [xl]

1904 Bainbridge was elected as Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and a Fellow to the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. [xli]

15 September 1904, Bainbridge sailed from London, with an extended tour of German Colonies in East and South-West Africa, and then on to Australia, ‘under engagement’ to explore the Fly River District of New Guinea. [xlii] According to a (1906) article in the Straits Times, Bainbridge went to Germany (in October 1904), before going to visit German Colonies in Africa.

21 December 1904, Bainbridge lectured at the South Grafton Public School (his father having died (2 September), without them having reconciled). Most significantly the advertised topic for this talk was ‘Land of the Black Jew’, before he had been to New Guinea to make his ‘discovery’, strong evidence the reason for his ‘expedition’ was all a bit of a sham, and that he knew in advance what he would find (and possibly based on his earlier (1896) visit). Doctor Henry had been at Bainbridge’s bedside when he died (in April 1922), having just come back from China (in the same year as a Chinese Civil War). When pressed on the matter of Black Jews in Papua Bainbridge is reputed to have replied, ‘They served their purpose Doctor, they served their purpose’.

1905: this, the Centenary of Trafalgar, was a ‘breakthrough’ year for Bainbridge. His expedition to the Fly River District, New Guinea, took place in March/April 1905. His reported ‘discovery’ of the so-called Jewish tribe of Papua created considerable interest and controversy, and gave him profile as an ‘Anthropologist’, subsequently used as his ‘cover’ for his various ‘snooping’ activities around the world. That other ‘agent’, T.E. Lawrence (who also had a gift for languages), had used ‘anthropology’ as cover for his spying and sabotage work in the Middle East, in the lead-up to World War I.

22 May, Bainbridge had returned to Sydney, having joined the ship Airlie on Thursday Island, and gave lectures in Sydney and Goulburn (where he had friends). On 26 June, at the Debating Club at Goulburn Library the topic is ‘The Japanese Alliance with Great Britain’, or more specifically ‘It is in the best interests of the world that Great Britain should renew her alliance with Japan’ (just prior to his Japanese visit).

11 July 1905, Bainbridge is awarded an ‘Address’ in the Council Chambers of his old town, Grafton, chaired by his friend Dr T.J. Henry, and signed by local dignitaries (including a young Earle Page), an incredible turn-around for having departed the town in ignominy some eight years previously.

5 August 1905, Bainbridge sails for Japan and China on the German ship Willehad, bound to Yokohama via German New Guinea, New Britain, and Hong Kong. The Russo-Japanese Naval War officially ends (5 September), at the Treaty of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, preside over by President Roosevelt (affirming a Japanese presence in Manchuria and South Korea).

September, Bainbridge was in Kaifeng, the old Imperial Capital of China (where the Dowager Empress had sheltered when foreign powers had occupied Peking/Bejing, close to Manchuria, over which Russia and China had just stopped their arm-wrestling), ostensibly searching for ‘Chinese Jews’ (as later published in National Geographic Magazine, 1907).

23 October 1905 (two days after the centenary of Trafalgar), Bainbridge returned to Nagasaki, and stayed in Japan for a couple of months, and visited the Ainu. In the contest of the recent Naval War (he had met Admiral Togo, [xliii] who had trained in England on the decks of the Victory, and had a significant Nelson Complex). One newspaper report (from the time of his Japanese visit) was from Kure, a top Naval District in the Hiroshima Prefecture, [xliv] where he could have met Admiral Togo. In the American collection of Bainbridge photographs there is one (dated December 1913) of Bainbridge’s New Guinea ‘contact’, ‘Captain’ Isokichi Komine (with local knowledge German naval ship moorings in the New Guinea region (standing), and a draft chapter on him in the American papers), and Admiral Kamimura Hikonojoo (seated).

In Japan in 1905 Bainbridge had also lectured at Waseda, Okura and other universities, and was received by Count Okuma (founder of Waseda University, who served as Japanese Prime Minister from 1914 – 1916), [xlv] and had visited the Imperial Palace to be decorated by the Emperor for his ‘contributions to education’. [xlvi] Not bad for an alumus of Grafton Gaol.

December 1905, Bainbridge is reporting his intentions to visit the old Jewish communities in Cochin, in what was then part of British India (as later published, with photographs, in India Today).

1906: In January Bainbridge is in Singapore, on his way back to London via India, and had visited Jahore (sometime before 18 January), and was in Colombo (2 March). On 21 May he was in Simla, India, in the Himalayan foothills (and venue of a viceregal lodge). This could have been his best opportunity to visit Tibet, just after the April signing of the Anglo-Chinese Convention for treatment of Tibet. Nina always said Bainbridge had been to Tibet, and there were Tibetan prayer flags in the American collection (and he was writing letters to Francis Younghusbnd in 1914).

July, Bainbridge is back in London for an exhibition in September. He returned to Hong Kong in November, and gave a repeat lecture (17 November) on ‘The Land of the Black Jews’ at the Lyceum Theatre, Shanghai, in northern China, with Consul-General Sir Pelham Warren presiding, [xlvii] then must have returned to London, as this ties in with a listing (unknown date), of him sailing from Southampton to New York on the St Louis. In late December he is in Toronto, Canada, using some of his own photographs to give an illustrated lecture (of vivid ‘word pictures’ of New Zealand, Fiji, Solomon and Gilbert Islands, and Papua) to a large audience at the Metropolitan Church, and other locations in Canada.

1907: bigamously married (8 January) Helen Marie Christiancy (of Toledo, Ohio) in Ottawa (family legend has it they were married in Bertie Township, Welland County, Ontario, Canada). They return to London at the end of March, and Bainbridge gives a talk to the Society of Women Journalists (10 May) at the Hall of the Society of Arts, with the popular novelist, Mrs Arthur (Henrietta) Stannard (‘John Strange Winter’) in the Chair (on whom he would later write a biography). On 27 May he is elected to The Japan Society, and a letter of introduction to Baron Kikuchi. [xlviii]

Their first child, Oliver St Clair (variant spelling to Andrew St Clare) Horatio (nod to Nelson) ‘Bungy’ Bainbridge was born (in July). Later that year (unknown date) he lectured (under the patronage of King Edward and Queen Alexandra), for the purpose of erecting a hospital for the benefit of distressed gentle folk. [xlix] On 12 October, the family (of three) sailed on the St Paul from Southampton to New York, [l] and is in New York for most of 1907/8/9.

1908: listed as speaking (in March) at the Women’s Republican Club (New York), and The Women’s Republican Association (1 April), and on ‘Hidden Jewish Tribes’ at the Congregational Temple Ez/Etz Chaim, New York (9 April), and The Devil’s Note Book (dedicated to Helen) is published in New York. 23 June, Barton Leon (‘Bubbles’) Bainbridge (Baron’s father) born in New York.

20 August 1908, the Great White American Fleet came round the bottom of Cape Horn to visit American Possessions in the Pacific (intended as a sign of American capacity in the region, as balance to the German and Japanese presence), with R&R in Sydney, New South Wales, forging the first important links in the Australian-American alliance. 27 November, Bainbridge gave an illustrated lecture, ‘The Savage South Seas’, in the new Masonic Temple in Washington DC, before the National Geographic Society, to a very large crowd, and received a standing ovation.

1909: still in New York, Bainbridge is promoting his ‘Travel Club’, with Baron Otto/Botto von Koenitz as its ‘President’. Initially meeting in the homes of wealthy women, it had been billed as a ‘great international movement … to do with the interests of peace’ (very much in the style of (1917) New York Mayor’s Committee, set up for entertaining British and French connections), with plans to establish branch clubs in London, Paris and Berlin, Germany (why did my mind go ‘bing’?).

A Chinese banquet had been arranged at the Hotel Plaza to celebrate its first year of operations, with ‘Professor’/‘Dr’ Bainbridge giving a talk (27 April) on ‘The Heart of China’ to a high-level guest list: including Andrew Carnegie, anglophile Joseph H. Choate, Wu Ting Fang, Mrs Walter Fern (Ambassadress, from the Court of Romania), The Marquis de la Rochebriand, Samuel Clements (Mark Twain), Dr Walter Bentley (‘holy warrior’ against Germany in World War I), Dr Rev Josiah Strong, John Temple Graves, and the American poet Edwin Markham. That Bainbridge had given a talk with Mark Twain and Edwin Markham in the audience is one for the books.

Andrew Carnegie needs no introduction, and was to set up his Foundation (a foreign-policy think tank in Washington DC) the following year (1910), but more significantly for the Bainbridge story he was the Chairman of the American Committee of the Peace Centenary book, and Bainbridge, because of his Pan-Atlantic connections, may have been ‘sounded out’ as editor of this book the previous November, when he was in Washington DC.

At first glance Bainbridge’s ‘Travel Club’ all seemed quite innocuous, but the use of the word ‘peace’ in this context (linked to all of Bainbridge’s other ‘peace’ references) made me assume it was all some kind of ‘front’ to help counter German influence in America. And the invitation of authors into this group, as well as A-listers, was to be echoed in the establishment of the (1914) British War Propaganda Bureau (not publically known until 1935).

But nothing in the ‘Travel Club’ was quite as it seemed. For Bainbridge was not a ‘Professor for a start, and Koenitz was not a ‘Baron’, with a castle in Thuringia, but a twenty-seven year old ex-convict (ouch) with an S-shaped scar on his forehead. Keonitz had been wounded in the leg in the Boer War, while fighting with the Boers (supported by Germany), when the English had caught him and branded him on the forehead with an ‘S’, for ‘spy’. If that is starting to sound a bit dodgy, then Bainbridge was implicated in introducing Koenitz to an older wealthy spinster, in anticipation of some form of remuneration.

1910: in New York until 14 February, when Bainbridge travels back (alone) to England (via Ireland) on the SS Merion, possibly escaping the ‘heat’ from the Von Koenitz matter, and may have spent time in Ireland. On 8 April Bainbridge has an interview with Lord Lamington, [li] who reports (25 April) that he has written to Sir Sydenham Clarke, the Governor of Bombay/Mumbai. Lord Lamington, apart from his stint as Governor of Queensland (1896 – 1901), had been Governor of Bombay (1902-3). As a young man he had been sent by the British Government to ‘explore’ the region between Tonkin (Vietnam) and Siam (Thailand), with the view of possible ‘annexation’, to try to limit French colonisation in the area.

27 April, Bainbridge, apparently alone (Helen and the boys join him in India at a later time), departs for India on the City of Colombo from Liverpool (and I am so impressed with his get-up-and-go). [lii] Just prior to his departure for India the late King Edward VII (died 6 May), had presented Bainbridge with a beautifully autographed photograph (from ‘Bertie’, for projected inclusion of a projected book on the ‘Princes of India’). [liii]

On the day of a posting (9 June) of a legal notice in the New York Times regarding his impending divorce, he is in Colombo, on his way to India to complete his work on the ‘Princes of India’. [liv] This appears to be an ‘official’ and relatively prolonged visit, with the boys going to school for some time in India, most probably in Bombay/Mumbai, while Bainbridge travelled about the countryside, and met the Dali Lama (in exile in India), and was entertained by various Maharajahs.

Some of the documented places he had visited in (1910) include: Trivandrum (14 August), Quilon (c. 17 August), C/- Post Master, Agra (October), State Guest at Ruhal Mahal, Kishengarth, Bhopal (29 November), and Jaipur (2 Dcember). On 30 November he is divorced from his first wife in New Zealand (decree nisi in three months).

1911: Bainbridge and his second family remain in India for nine months. At one point in this year (unspecified date) he had been entertained for 16 days as guest of the Gaekwar, Maratta Court, Baroda (Vadodora). [lv]

17 May, from an article published in The Oriental Review, he is staying in a suite of rooms at the Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, Bombay/Mumbai (with an almost Emma Hamilton’s attitude to ‘show’ and money, and he always dressed exceedingly well, so you can see why he was always short of cash), ‘having just completed an extensive tour of British India and the Native States’. [lvi]

By September he had returned to London, [lvii] when in (late September) he was ‘compelled to leave for the United States of America’. [lviii] The word ‘compelled’ implies something high-level, most probably to do with the ‘Peace Centenary’ Project.

By October he is living in ‘The Mill House’, Virginia Water, and Surrey, UK (where Nelson’s house ‘Merton’ had been. While in England, now apparently passing himself off as an American, he had addresses members of the East India Association in the Caxton Hotel, London, on ‘Some Anglo-American Impressions on India’. [lix]

25 October Bainbridge and his son, aged three, departed Liverpool, England, on the Merion, for Philadelphia, USA, [lx] most probably to do with the Centenary project, or his son to spend time with his grandparents.

5 December, in Melbourne, Australia, Oliver’s brother, the Rev. Gordon Nelson, Vicar of Panmure, had married Miss Isobel Bant, eldest daughter of Mr William Bant of ‘Kia-Ora’, Panmure. [lxi] There suddenly appeared to be money about, and they went of a world trip for their honeymoon, at a point when there seemed to have been problems between Helen and Oliver.

1912: 22 of January, there was a letter to Bainbridge from the President of the Toledo Museum in which he refers to an earlier letter (of 19 January), saying sorry to hear that Bainbridge had been ‘wrenched from the loving grasp of his wife last Wednesday evening’. [lxii] As used here the word ’wretched’ is stronger than for a normal parting. Because of the Toledo connection this had to be a reference to Helen, as this is where her people had come from.

Miles Bainbridge had since found a clipping in an Illinois newspaper (undated, 1912), in which ‘Sir’ Oliver (the man, it seemed, really had no sense of shame) was reported to be leaving on a two year journey … [to India?] … with a ‘private secretary’ from Illinois (assumed in this case to be a female). Had the 1912 ‘fracture’ in the marriage been caused by some ‘inevitable girl’ from Illinois? Helen was spirited and brave, and had been joined Bainbridge in his travels (of some 50,000 miles) in India (1910/11), where, according to Barton Bainbridge Helen had once spent time inside an Indian harem (with Oliver’s full support), to study the institution, and the practice of ‘Purdah’ (the screen hiding women from view), and wrote an article about her experiences. [lxiii] Whatever the cause, they had certainly come back together after that.

Perhaps the problem had been Bainbridge’s ‘work’. He was supposed to have been in India for a lot of 1912/13, but nothing has ‘come up’ in the usual places as for other years, with an apparent ‘radio silence’ from news-hound Oliver. Was he somewhere else? On 8 October Montenegro had started the First Balkan War.

30 October, Bainbridge is in London again, when he lectured at the opening meeting of ‘The China Society’. During this same year Bainbridge had published ‘Peace’ (an Essay, 1912), and The Heart of China (1912).

At some unknown date (1911) he had ‘warner the Kaiser … that if he tried [to] carry out his plans [of military build-up?] he would find destruction’. [lxiv] This was followed up with an article in The Empire Magazine (December 1912), in which Bainbridge, talking about preparations being made by Germany had said they ‘are neither necessary nor intended for the protection of German commerce, but to destroy England’. [lxv]

1913: marks the Publication of his book India Today. From a 1914 report in a local (Grafton) paper, Bainbridge gave a series of lecture tours in the chief towns of England (in 1913), then went to the Balkans at the end of this tour. [lxvi]

22 January, Baibridge talked at the Liverpool Geographic[al] Society on ‘Southern Natives and Cannibalism’. While in the North West area (1913) he lectured to an Ambleside audience, Westmoreland, Cumbria, on ‘Mysterious India’, with a 31 January talk (Liverpool?) on ‘The Land of the Moa’. [lxvii] 7 February, spoke to young people (about New Zealand) at King’s Hall, Coleman Institute (under the auspices of the Redhill Literary Institute, Surrey (?)), and gave another lantern lecture (on New Zealand, 28 February) to the schoolchildren of Reigate, Surrey. [lxviii]

30 May, ‘Treaty of London’, preliminary peace deal to end the First Balkan War, between the Balkan allies and the Ottoman Empire (eliminating the Ottomans from most of Europe), when Bainbridge has a meeting with Mr J.K. Headley, Minister of Public Works for the state of Liberia (?). [lxix]

29/30 June, Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its gains in the First Balkan War, begins local attacks against Greek and Serbian positions in Macedonia. Greek and Serbian forces counterattack, and Romanian and Ottoman units invade Bulgaria. [lxx] The penny has now dropped for me. There are a lot of Balkan war photographs in the American collection, along with the mandatory groups of happy peasants, suggesting Bainbridge must have been on the scene.

Bainbridge’s address for June and July is C/- ‘The Empire Magazine’, 4 Executer Street, Strand WC, London. He had also been corresponding (1913) from the 3rd Baron Monkwell (appointed 3rd Secretary of the British Diplomatic Service (1902), and who, in 1911 had published a book (1911) on the strategically-important French Railways (for movement of troops and supplies). [lxxi]

10 August, a defeated Bulgaria sues for peace, and loses ground in the ‘Treaty of Bucharest’, with a Carnegie Commission into the Balkans (August/September), seeking causes of the Balkan Wars (with Carnegie links to Bainbridge from his New York ‘Travel Club’ and the Centenary Peace Project).

During August/September/October Bainbridge is living at ‘The Firs’, Eversham Road North Reigate, Surrey (back in Nelson Territory), and gives more talks, one with a reference to ‘World Friendship’ through the Queen Alexander League, that he was unable to give owing to illness, [lxxii] and another (14 November) on ‘Mysterious India’. [lxxiii]

1 December, Bainbridge pops up in Belgrade, as ‘personal adviser’ to Tsar Ferdinand I of Bulgaria (with the rank of Ambassador). While in the Balkans he had an audience with ‘Carmen Sylva’ (Queen Elizabeth), Literary Queen of Romania (who had said she never changed a word/line in any poem she had written down), who had received him at Bucharest. [lxxiv]

1914: 14 January, Bainbridge is at Pera Palace, Istanbul, Turkey. On 5 March he was in Athens (and was later writing to King Constantine of Greece, ‘who had received him [Bainbridge] at different times’). [lxxv] On this same day (5 March) Every Day with Another Mind was at ‘hand’, in London.

28 March, Bainbridge receives a letter/note from Ferdinand asking him to accompany Queen Eleonore (of Bulgaria) to America (as part of her entourage), [lxxvi] to study nursing techniques, no doubt in anticipation of a looming war. On 10 April ‘Professor’ Oliver Bainbridge, Helen, and the boys depart from Southampton on the Amerika for New York. On 19 April he is in New York with a ‘Letter of Introduction’ from Charles J. Vopica, Woodrow Wilson’s American Ambassador to the Balkans, [lxxvii] fielding questions about some of the politics of the Queen’s visit, and whether he is a ‘professor’ not, then he is ‘sprung’ (24 April) at a press conference at the Ritz-Carlton (more high living) about the marriage of ‘Baron’ von Koenitz to Miss Louise Ewen. [lxxviii]

Bainbridge is part of a ‘gracious reception’ with President Woodrow Wilson (date not specified, probably in April), when the Queen was in the ‘east of America’. [lxxix] On 12 May, a (Devon) newspaper is reporting the publication of Bainbridge’s ‘Peace Centenary’ book. [lxxx]

3 July, Bainbridge and his family set sail for Europe, [lxxxi] and returned (24 July), [lxxxii] living at ‘Trescoe’ Reigate, Surrey, England.

28 July, Bainbridge was in Ghent (Belgium), making arrangements for ‘Centennial Celebrations’ when World War I broke out. He immediately returned to England and was appointed ‘His Majesty’s Royal Commissioner’, [lxxxiii] based in London, and lectured throughout Britain on behalf of various War Funds. From an analysis of his activities, associates, and publications of this period he was certainly associated with the British War Propaganda Bureau, [lxxxiv] which after the style of Bainbridge’s (1909) New York ‘Travel Club’, had invited authors to its foundation meeting (and later artists), to help promote their cause.

2 September, writer and MP Charles Masterman, had invited 25 leading British authors to Wellington House. One of these was Sir Arthur Conon Doyle, university friend of Bainbridge’s friend and mentor Dr Thomas Henry, who had been the Hon. Secretary of the English Committee of the 1812 -1814 ‘Peace’ book, edited by Bainbridge.

Francis Younghusband (of the Tibet expeditionary forces) had recruited musicians and composers to his associated ‘Fight for Right’ Movement (August 1915), with almost ‘holy war’ overtones. Edward Elgar had composed the song ‘Fight for Right’ for them, from the text of William Morris. Hubert Parry (who had written to Bainbridge), composed the song ‘Jerusalem’ (from the poetry of William Blake), for the Movement’s first performance (but later withdrew his support from the Movement because of its more jingoistic elements). Early supporters of the ‘Fight for Right’ included Lord James Bryce (producer of the report of ‘Alleged German Outrages’ (12 May 1915), whom Bainbridge had written to [lxxxv] and there were lurid notes of alleged German atrocities in the American Bainbridge papers), Thomas Hardy (novelist), and Poet Laureate Robert Bridges (who had written to Bainbridge on at least two separate occasions).

Bainbridge’s war pamphlets included: ‘The United Balkan States’ (August 1915) ‘The Philosophy of War’, ‘While Bulgaria Hesitates’, ‘England’s Arch-enemy, the Kaiser’. His War Letters are a compilation of his writing to European Royalty and Balkan contacts, to English, American, Canadian and Australian politicians, to Count Okuma in Japan, and to Indian Administrators and Civil Servants, with the one aim of trying to get them to join the allied cause. That he had been some form of English ‘asset’ is most evident in this book, with their frequent references to German agents, troop movements and specific skirmishes, and intemperate descriptions of the Germans (and of the Irish, after the 1916 uprising). Other publications include a small booklet called Little Stories from Other Wars (for ‘Khaki’, Prisoner of War Fund, London), and he later gave talks on such titles as ‘German Intrigues’ and ‘Our Ally Japan’.

15 August, long-awaited opening of the Panama Canal, which completely alters the naval ‘balance of power’ in the Pacific (and more so in World War II).

From September to December Bainbridge lectured around England: 23 September, ‘Bulgaria and Tsar Ferdinand’, Newcastle (on Tyne), 16 October, [lxxxvi] Exhibition of Indian Princes (in London?), [lxxxvii] 2 November, repeat lecture (?) on Bulgaria, Newcastle (on Tyne), 5 – 10 November, [lxxxviii] 21 November, ‘The Kaiser’s War’, Bristol, Gloucestershire, [lxxxix] and to appear at the Hippodrome (Great War Theatre, London, opened 1914?) on Sunday next. [xc]

1915: lectured night after night in various centres on behalf of the National Relief Fund, when he intended to go to the front (most probably Gallipoli, as Barton told me his grandfather had talked to the troops there), where he caught up with his friend Dr Henry (stationed in Egypt), [xci] and there are Gallipoli photographs in the Bainbridge collection.

British, Australian and New Zealand forces had landed at Gallipoli on 25 April, and withdrew in December of that same year. General Sir Ian Hamilton (British Commander of the Gallipoli landings) is writing to Bainbridge (21 July) to thank him for his kind offer … and [would] let him know if he [could] see a possibility of arranging for a lecture [to try to help lift troop morale]. Hamilton had been attached to the Japanese Imperial Forces (as part of the Indian Army, during the 1904 – 1905) Russo-Japanese War. More linkages.

Bainbridge had written to Younghusband, ‘offering support’ quite early in the piece, with a reply (17 September 1915), [xcii] then Bainbridge wrote back re ‘speaking at some of his meetings’. [xciii] Some of Bainbridge’s 1915 lectures included: 4 May, (illustrated talk on ) ‘Bulgaria’, Reigate and Redhill, 7 May, ‘Bulgaria’, repeated at Bath, 5 October, ‘India and War’ at Surrey school, 15 October, ‘The Bulgarians’, Dover, 19 October, ‘The Bulgarians, and Impressions of King Ferdinand’, Hull, 3 December, ‘Serbia’, Glasgow (with reference to Cork, Birmingham, and Hull), 26 December, ‘The Balkan Problem’, Liverpool. [xciv]

27 August, Bainbridge had received a large autographed photograph from King Nicholas of Montenegro. That month (August) Bainbridge had published his essay, ‘The United Balkan States’, suggesting how a union of the Balkan States could hold off Germany’s capture of Constantinople, an important strategic, military, and naval base.

11 October, Bulgaria, having lost territory in the ‘Treaty of London’, now turns to the Triple Alliance, and the Bulgarian army attacks Serbia. Bainbridge resigned from his service to Ferdinand, with a most undiplomatic letter sent to him.

1916: Bainbridge rails against the ‘Easter Uprising’ (Easter 1916) in his ‘War Letters’, talking (in a letter to James Redmond MP) about ‘Sinn Fein ‘murders’ financed by Germany and working to bring down the British Empire’. [xcv] 5 June, death of Lord Kitchener, on the sinking of the HMS Hampshire west of the Orkney Islands (possibly not because of it hitting a German mine, but because of explosives secreted by Irish Republicans). I could not find any advertised Bainbridge lectures in England for the first part of this year. I have no evidence, but given tang of his War Letters (with some of them written to people in Ireland), had Bainbridge been in Ireland at this time?

This is the year of his publication of John Strange Winter, and Bainbridge is starting to plan for a ‘Scientific Expedition to the South Pacific’, in anticipation of a win against Germany in the war. Evidence for this comes from a letter sent with a copy of this book to Sir Francis Fleming (British Colonial Administrator in Ceylon and Hong Kong), on the letterhead of ‘The Bainbridge Expedition to the Southern Seas’. [xcvi]

Bainbridge continues his lecturing throughout the second part of the year: 24 June, ‘Kossovo (sic) Day and the Serbians’, St Mary’s Hall, Coventry; 19 September, ‘British and German Natives’, and ‘Turkey and the Turks’, Newcastle on Tyne, 5 November; ‘Land of the Sultans’ (with aid of lantern slides), back at Newcastle (his fourth known visit); 29 December ‘The Savage South Seas’ (with a sub-text of the German Colonies) Royal, Royal Colonial Institute London), presided over by the Hon John Jenkins, formally President of South Australia, and later supporter of Bainbridge’s ‘Expedition to the South Seas’. The gold medal for the best essay was won by Victor, J. Wilmoth, aged 9, for the best essay finishing with the sentence, ‘The South Sea Islanders, although they are supposed to be savage, could teach the Germans a lesson in kindness’. [xcvii]

Perhaps he knew someone at Newcastle (on Tyne)? In some of my computer searches for Bainbridge’s sons from his second marriage (before Barton had contacted me), the name ‘Oliver Bainbridge’ had surfaced on occasions in the north of England. Could this have been a by-product of his time up-north, or a child’s name inspired by his talks?

1917: publishes ‘The Worn That Turned’ (illustrated propaganda pamphlet), and Shells from Many Shores (unsighted, location unknown), and lectures, 17 January, ‘Bulgaria’, at Hull (as substitute for Mr Will Crooks MP.

8 March, beginning of the Russian Revolution (called the ‘February Revolution’, because Russia used the Julian calendar until February 1918. More radio silence on the Bainbridge news-hound front in UK for the rest of the year. Given the established pattern of him visiting conflict zones, is it too much to image he had visited Russia, considering he had been there before and is believed to have had some proficiency in the language.

21 December, back at the Royal Colonial Institute for a talk on ‘Outposts of Empire’.

1918: 28 February, lectured on ‘India, the Pivot of the Empire’, Literary Institute, Hull, [xcviii] with a follow-up report from Hull, 25 May, of his expedition to New Guinea. [xcix]

Returns to Australia, mid-year (date unspecified) with his family. [c]

9 July, lectured on the ‘Kaiser’s War’ at the Canadian Club, Vancouver, in Canada on his way back to Australia, as Head of an Expedition (of eight scientists) on their way to New Guinea, to ‘survey’ Papua and the Solomon Islands. His intention had been to survey the islands first, and then come back to Australia, but the Influenza [Pandemic] and shipping difficulties compelled him to reverse his itinerary (I’m not sure what happened to the scientists). [ci]

26 August, gave a ‘thrilling’ (home town) lecture in the Theatre Royal, Grafton. [cii] 18 September, received by His Excellency, the Governor, and given a Civic Reception by the Lord Mayor at the Sydney Town Hall, and lectured in aid of the Lord Mayor’s Fund. [ciii]

On his return to Australia the ‘retired spy’, opting for a more simple life, had purchased (October?) a farm at York Estate Penrith, to head north again to lecture for the benefit of the Red Cross. [civ] 2 November, working on a publication ‘Why the German Colonies must not be Restored’’ (with parts of the manuscript retained by the American family). [cv] 7 November, lectured at South Grafton (to a large crowd), on ‘Turkey and the Turks’ (with the proceedings going to the Red Cross), and was presented with (another) ‘address’ by the citizens, and his mother given a floral token. [cvi] Four days later (11 November), the monumental ‘War to End all Wars’, came to an end.

1919: working on a book on ‘The Coming Struggle’ (with Germany). The book does not seem to have materialised (apart from a number of lectures on the topic), the basic thrust of his arguments being that another war with Germany is almost inevitable (and came to pass in 1939).

1 February 1919, a newspaper report said Bainbridge was claiming that Sinn Fein (IRA) had attempted to kill six of his jersey cows, poultry … and were destroying his fruit trees, but ‘would never silence him’. [cvii] Apart from ‘the underground and futile tactics of some traitors to injure him’ it was certainly not all ‘fun and games’ back on the farm, as late in 1918 or early in 1919 he’d been bitten by a black snake, suffered illness from an inoculation, then in February, master ‘Bubbles’ Bainbridge (Barton’s father Barton Leon), accidentally shot himself in the foot.

15 March his poem ‘Coup D’Etat’ (of a stolen kiss) was published on the first page of the Nepean Times. [cviii]

Lectures/interviews conducted during this year include: 24 March, India, The Pivot of Empire, Empire Literary Society (in the old sandstone Department of Education building, Bligh Street Sydney, where I had meeting when I worked at the Museum in the 1970s), with Mr G.F. Earp MLC (who attended the Bainbridge funeral) presiding; 27 March, ‘German Secret Societies’ (in all parts of the world), Millions Club (established in 1912 with the aim of making Sydney the first Australian city with a population of one million, which later became The Sydney Club (where I once gave a talk on ‘Poetry associated with the Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney’); evening 27 March, repeated ‘India’ talk for the benefit of St Steven’s Church, Penrith, to a ‘crowded hall’; 4 April, another repeat of India talk, location unknown; 30 April, entertained by His Majesty the Raja of Pudukkottai (visiting Sydney at the time); 20 June, ‘Our Ally Japan’, Empire Literary Society (St James Hall), with the Hon Sir William Cullen presiding; 24 June, ‘Japan and the Japanese’, local Penrith schoolchildren; 27 June, repeat of Our Ally Japan, St James Hall (with Japanese Counsel Mr Shimizu present (‘showing [Bainbridge] lantern slides of the Japanese Emperor and Empress, some naval ‘generals’ [more Nelson influence], scenes of Tokyo, types of Japanese women and girls, various beauty spots and industries (a measure of ‘capacity’)), 29 June, interview with William Holman, Premier of New South Wales, on Bainbridge’s projected large work (on Australia), ‘Britain in the Southern Seas’, with Australia destined to play an important part in the history of the British Empire (a book that did not eventuate); 24 July, free lecture (on Japan) for teachers and children in St Stevens Hall Penrith; 25 July entertained by Mr Shimizu and Mrs Shimizu at The Australian Hotel (prior to their departure for Japan). Other guests included the Counsel-General of the United States and Mrs Brittain, Mr G.F. Earp and Mrs Earp, and Mr [L.P.] Curno and Mrs Curno; August, Japan, another lecture (on ‘Japan’), Empire Literary Society (commented on by Mr Zomoto, leading Japanese journalist with official connections). [cix] Japan was obviously Bainbridge’s ‘flavour of the last few months’’, and Japan was certainly interested in New Guinea.

* * *

Bainbridge’s proposed expedition to Papua had been deferred. [cx] In late August Bainbridge departed on a trip to Victoria, South Australia, and Western Australia instead, to collect information and photographs for his projected book (on ‘Britain in the Southern Seas’).

28 August, Mr Tudor MHR, Mrs Tudor and Oliver Bainbridge lunched with the Governor-General and Mrs Munroe-Ferguson at Government House, Melbourne, with a Reception at the Town Hall, Melbourne, as guest of the Lord Mayor. Bainbridge was then introduced to the Senate and the House of Representatives (then in Melbourne, with no mention found in Hansard), and joined with the Mayor in an official welcome for the Prime Minister, Mr W.M. Hughes. [cxi] Hughes had returned from the Peace Conference in Paris, where he’d opposed President Woodrow Wilson to obtain full control of German New Guinea for Australia, with the power to exclude Japanese entry, with obvious ramifications for World War II. All very much Bainbridge ‘territory’ and Bainbridge stayed in Melbourne for several weeks.

18 September, lectured to senior high school children in the Assembly Hall (of Parliament?) on ‘Our Ally Japan’, and the Minister of Public Education (Mr Hutchinson) wrote to Bainbridge (19 September 1919) to congratulate him on his ‘skills in holding an audience of young people and adults’. [cxii]

23 September, arrived in Adelaide, and staying in the South Australian Hotel, and returned to Melbourne 25 September, by the express. [cxiii]

7 October, lectured to a large audience at the Melbourne Town Hall on ‘Our Ally Japan’, when the Lord Mayor referred to him as ‘Ambassador-General of the Empire’. [cxiv] On 8 October Bainbridge had an audience with Prime Minister Hughes at Federal Parliament House (Melbourne), where they discussed matters relating to Australia and the Empire. [cxv] One assumes that New Guinea was on the agenda. At a following reception in the Town Hall he is now playing down the quality of Japanese imports, as not being of the same quality of the samples. [cxvi]

15 October, Bainbridge is back in Adelaide, and entertained by His Excellency, the Governor of South Australia at Government House, and was Guest of Honour at the Commonwealth Club, with a luncheon at the Adelaide Town Hall. In Adelaide he was still talking of ‘plotting Germany, already planning for another war, and of widespread intrigues and conspiracies’, and described in the local press as a man who ‘never scruples to express strong thoughts in strong language’, [cxvii] his ultimate undoing it would seem.

18 October, Bainbridge had returned to York Estate after a strenuous tour of several weeks, to news of the potential of some big property deal (for someone who was always broke) that did not seem to materialise. [cxviii] Then another of his valuable jersey cows had been killed (by apparent injection in the leg), the fourth such cow to have now died under mysterious circumstances.

Prior to 15 November he is elected as an Hon. Member of the Australian Literary Society (established Melbourne 1899), that went on to become the Association for the Study of Australian Literature, [cxix] no record of which has been found to date.

1920: 8 January, Bainbridge wrote to Premier Holman (on the letterhead of ‘The Bainbridge Expedition to the South Seas’), pushing his forthcoming publication and listing his supporters, and then railing against the IRA who have now poisoned six of his cows, prized poultry and other innocent creatures, [cxx] and apparently had a meeting with the Premier and his local member, Mr William Zuill MLC.

1 February, Bainbridge wrote a strange, apparently paranoid letter (and possibly not so paranoid in retrospect) to Premier Holman, referring to their previous meeting (in the presence of Mr William Zuill MLC), ‘hoping the lies of Sinn Fein (in insulting anonymous letters trying to stop him carrying on his work) had not had any affect (on the Premier’s judgement) … and that he was in possession of some startling information regarding the designs of the Vatican [towards the British Empire] … but he had made up his mind to expose the twin enemies of the Empire: Germany and the Vatican … and that no organisation, secular or religious, would ever put a padlock to his lips’. [cxxi]

5 February, Premier Holman declines to see Bainbridge because of intense work pressure (with a memorandum saying in was not conceivable [he] would be influenced by floating rumour). [cxxii]

At precisely this same time (early 1920), the Irish leader Michael Collins was setting up a special hit squad called the Twelve Apostles, having identified ‘G’ Division as the lynchpin of British intelligence. Bainbridge then informed the Premier he was supposed to be going to England in Early March, via other places. [cxxiii] His Visitor’s pass (No 4, that may have referred to his Railway Gold Pass) had expired, and was required to be returned. [cxxiv]

19 April, Bainbridge was writing an ingratiating letter to the new Premier, John Story MLA. His planned trip to England had been postponed. [cxxv]

14 June, letter from Sir Charles Rosenthal, Secretary, soon to the established anti-Sinn Fein ‘King and Empire Alliance’, delighted to have lunch with Bainbridge at Petty’s Hotel, on Thursday next at 1.15 pm. [cxxvi]

26 June, reported publication of Our Farm, [cxxvii] (unsighted, but with plenty of subsequent references to this apparently morphing book in the (local) Penrith Press). Since the 2017 publication of Lord Nelson, Uncle Oliver and I, I have discovered an early manuscript to this proposed publication (with more revelations of IRA intimidation at Penrith). [cxxviii]

Prior to 17 July, he was presented with an autographed photograph by His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales (Naval Cadet, 1907) [cxxix] By a strange coincidence, Bainbridge’s first wife’s sister’s boy, Hector Bolitho, for whom Bainbridge had brought back a pet monkey to New Zealand in 1901 (from China?), had accompanied the Prince on his tour of New Zealand.